“Illuminations of Isham Lane,” galenograph, 2023

In 1987, I enrolled in a poetry workshop with the American poet Marvin Bell at Centrum Foundation in Port Townsend, WA. We were given a poem assignment to craft that evening and read to the class the following day. The task was more about construction than content—repetition of words.

The following morning, I read my poem to about six men and six women. When I'd finished, the men were twisting and squirming in their chairs, looking at the floor, slightly uncomfortable, and the women were joyfully clapping and yelling, "Read it again!"

To this day, I have no memory of shaping the poem in my mind. Where did it come from? Years later, after reading the diary of my great-great-grandmother Frances Fowler Taylor, born in 1838 in Crawford County, Georgia, I concluded that I must have been channeling her spirit.

She married at fifteen and had six children with Willis Taylor, an older man marred from acute alcoholism and a nasty temper, inflicting upon his young wife endless pain and distress during the years they were together. In her diary, she writes about an event occurring within hours after her fifth child was born when her drunken husband threatened to cut her throat with his knife, Frances's nine-year-old daughter, Georgie, trying desperately to intervene. Eventually, the husband passes out. Frances writes: "With a cry to God for mercy, I sprang up. "Oh! Daughter, do not let him kill me!" I cried. "I don't know how I did it, but I took the knife away from him. I then thought that I would have to take his life or lose my own. Oh! What a terrible and heart-rending scene to behold—a woman about to kill her husband in self-defense. What must I do? Must I kill the man who I have loved so dearly, for whom I have forsaken father, mother, sisters, and brothers?

"Must I kill him, Georgie? Oh, tell me, must I kill him?"

"Oh, no, Mama. Don't kill him!" she cried.

Soon after this tragic event, when Willis apologized, hoping to mend the relationship, Frances refused, knowing the abuse and alcoholism would continue and the cruelty would increase. She left him, raising the children as best she could with little income. Later in her life, she moved to Brunswick, Georgia, and lived with her youngest daughter, my great-grandmother Lilla Belle, or Nanny, as we called her. After Nanny died in 1951, her children sold the big Victorian house at 1302 George Street. One of our relatives, inspecting the now-empty house, noticed a bulge in the wallpaper where a large bureau once sat in Frances's bedroom. Upon closer inspection and peeling away the old paper, she discovered Frances's diary beginning in 1885. Thanks to my brother and family historian, Bernard Garwood, her diary has been brought into the light. The question of why she hid it is fascinating. She wanted it found, but not until after she'd died. But why?

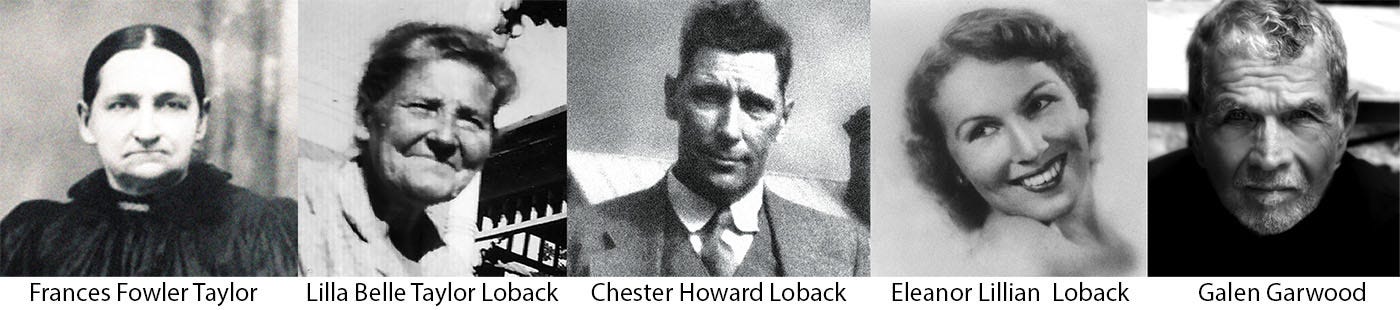

from right to left: Me, my mother Eleanor ( Ida Lane), my grandfather Chester Loback (PaChuddy), my great grandmother Lilla Belle (Nanny), and her mother, Frances.

In truth, I can't be sure who or if anyone I was channeling when I wrote the poem thirty years before the "Me Too" movement. I could have been, if such things are possible, channeling someone from the 16th Century or two weeks before I wrote the poem.

Still, I wish to dedicate the poem, as macabre as it might seem, to my great-great grandmother Frances Fowler Taylor and, additionally, to all women whose hearts, hopes, and potential have been diminished and bruised for no other reason than that they are women.

THE DEATH OF PETER BLACK

Elizabeth also buried the broken bottle with which she cut her husband’s throat.

It wasn’t mean, she thought, to end it all, to bury him with the marriage and the ring.

A broken heart’s hunger turns the shovel easily enough,

and every spade of dirt she put on him was a bruise he’d put between the sheets.

“Kindness from men,” she said, “is like a whistle from a hen;

it rarely happens.”

But when it did, she’d let him plow all goddamned night.

But no more, no more. Her heart hasn’t the hunger it had.

The eyes of the hen she put in a blue bottle with a silver whistle, locked

in a box without a key.

Elizabeth hums a song her mother sang, and from the window

she watches the weeds grow.

For the life of me, she wonders,

“Why can’t I remember his name?”

Thank you, Jo!

Thank you, N...